Literally! Hehe, the lame joke is because I’ve spent some time recently implementing shadow rendering. I chose to use the popular shadow volume technique, AKA stencil-shadows, because I liked its apparent simplicity. Indeed the overall concept is very straightforward, but just like with the more venerable shadow-mapping technique, there are lots of little details that can make or break an implementation.

I won’t go into the details nor write a full tutorial here, there are several other resources that do it very well, and for that, I’ll list them at the end of this post. What I’m going to do is just talk about some of the decisions and discoveries I made through the process.

Shadow Volumes

The architecture of shadow volumes is very neat: Clear the screen to black. Render an extruded volume defined by the silhouette of and object with relation to a light source. Use the stencil buffer when doing the volume rendering pass to count the pixels that fall inside this volume. In a second pass, if the stencil value for that pixel is not zero it means that that pixel is inside the area covered by the shadow volume. Leave the pixel untouched (black). Done!

So the first step is to compute a set of edge adjacencies for each triangle of each mesh. This process is far too expensive to be done

at runtime, so it must be done offline or as a pre-processing step. An efficient edge list construction algorithm is very important for

a shadow renderer. The number of vertexes that need to be rendered with the shadow volume is directly proportional to the number of edges.

Actually it can be up to (numShadowingTriangles + numEdges) * 6 vertexes. Times six because, for a point light, the shadow volume will

be composed of quadrilaterals. Since I only deal with triangles in my renderer, I have to break each quad into 2 triangles.

Well, it turns out that correctly computing an edge set for a non-watertight mesh is very, very hard. So don’t expect shadow volumes

to work with any type of 3D model. There are some approaches to address this problem, but generally I would suggest that you just select

a simple edge detection algorithm, such as the Half-Edge and make sure your geometries are closed. It is a lot simpler and is

one of those trade-offs that we can safely make in a game’s context. I actually took a peak into the Doom 3 source and based my edge

building code on theirs. One important thing to note on this is to make sure to remap the vertex indexes and ensure they

are unique (R_CreateSilRemap() / R_CreateSilIndexes()). Normally you are forced to duplicate vertex positions to add unique texture

coordinates/colors to a vertex. Building an edge list with such a mesh would be sub-optimal, resulting in a lot of duplicate edges.

The remapping trims down the number of edges.

Also worth reminding that shadow volumes won’t work for alpha tested surfaces, such as sprites and foliage. The actual vertexes are required for the edge list building.

The Vertexes

My whole implementation was inspired by Doom 3’s shadow rendering. I decided to do as they did and keep a system memory

copy of the “shadow vertexes”. What I call shadow vertexes here is a set of duplicate vertexes of a given mesh, with

expanded W coordinates for extrusion. This approach is commonly called the Vertex Program Shadow Volume and is explained

by Eric Lengyel in his book and by idSoftware in this paper.

This set of duplicate vertexes will increase the memory usage of the application. In my specific case, it adds about 1/2 of

each mesh to the total memory. You need two extra vertexes with [x,y,z,w] for each model vertex. Each model vertex for me has

4 vec3’s and 1 vec2, so the shadow vertex buffer has about half the size of the rendering vertex buffer.

Following is an excerpt of Doom 3’s shadow vertex cache setup code, with some irrelevant stuff removed. It is very simple but effective.

[Doom3] renderer/tr_light.cpp(150):

typedef struct shadowCache_s {

idVec4 xyz; // we use homogenous coordinate tricks

} shadowCache_t;

/*

==================

R_CreateVertexProgramShadowCache

This is constant for any number of lights, the vertex program

takes care of projecting the verts to infinity.

==================

*/

void R_CreateVertexProgramShadowCache( srfTriangles_t *tri ) {

shadowCache_t *temp = (shadowCache_t *)_alloca16( tri->numVerts * 2 * sizeof( shadowCache_t ) );

int numVerts = tri->numVerts;

const idDrawVert *verts = tri->verts;

for ( int i = 0; i < numVerts; i++ ) {

const float *v = verts[i].xyz.ToFloatPtr();

temp[i * 2 + 0].xyz[0] = v[0];

temp[i * 2 + 1].xyz[0] = v[0];

temp[i * 2 + 0].xyz[1] = v[1];

temp[i * 2 + 1].xyz[1] = v[1];

temp[i * 2 + 0].xyz[2] = v[2];

temp[i * 2 + 1].xyz[2] = v[2];

temp[i * 2 + 0].xyz[3] = 1.0f; // Vertex is not changed

temp[i * 2 + 1].xyz[3] = 0.0f; // Will be projected to infinity

// by the vertex shader

}

vertexCache.Alloc( temp, tri->numVerts * 2 * sizeof( shadowCache_t ), &tri->shadowCache );

}Another very attractive technique is to generate the shadow vertexes on-the-fly using a Geometry Shader,

as explained on GPU Gems 3. This would only require a small adjacency set to be added to the

index buffer (GL_TRIANGLE_ADJACENCY). I am yet to try this method. The only downside of it, seem to me, is that

still to this date some platforms don’t have Geometry Shaders, as is the case with OpenGL ES2 based devices and

PS3/Xbox360. But it surely seems like a nice optimization where the hardware is available.

Building the Volume

Once the edge set is built, a shadow volume can be generated with relation to a light source. Using the shadow vertex buffer

scheme mentioned above, you can work directly with indexes. This is important to reduce CPU => GPU traffic, since the shadow

volumes can be heavily tessellated. There are several optimizations that can be applied to this step. The most common but

effective being the use of some form of parallelization. Each shadow volume is independent of any other, so given a light

source and a set of objects, each volume may be constructed in parallel for that light source. This is a spot where a

rendering engine can be made parallel with a task/job approach. In fact, idSoftware did parallelize their shadow volume

construction code for Doom 3 BFG edition, the re-release of the original Doom 3. I believe the parallelization of this stage

of the rendering pipeline must have been crucial to ensure a smooth gameplay on the limited hardware of past-gen consoles.

Another sensible optimization is to parallelize at the instruction level using SIMD. It can be done quite easily since the shadow vertexes are vec4’s and a plane equation for a triangle can also be packed into a vec4.

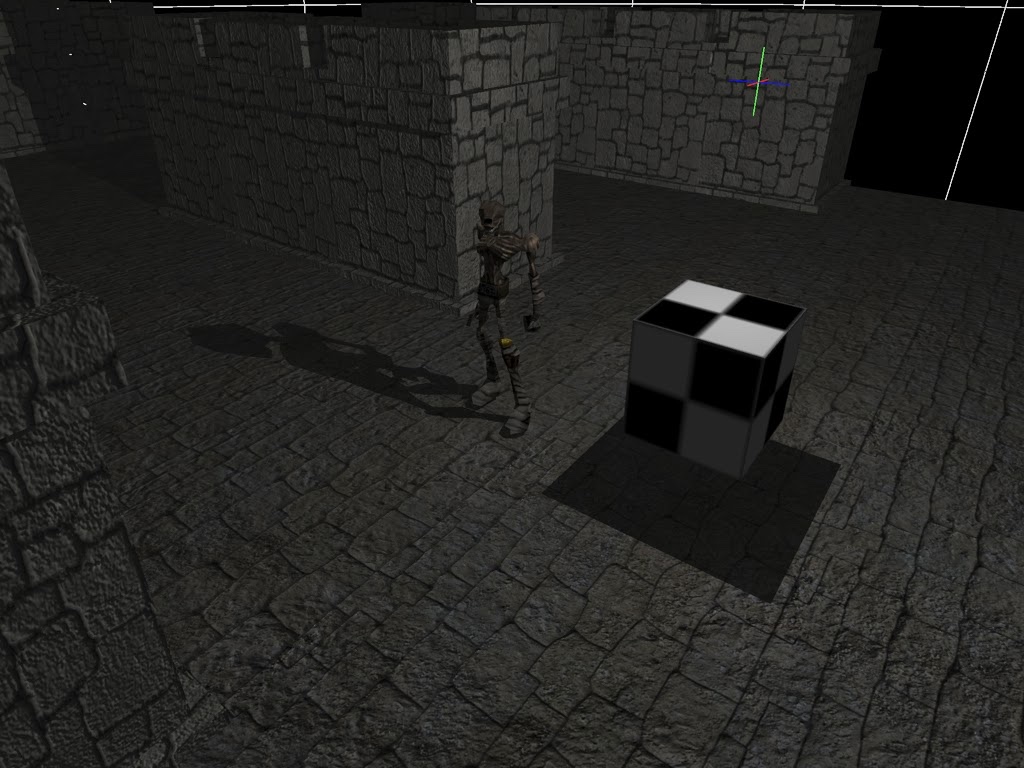

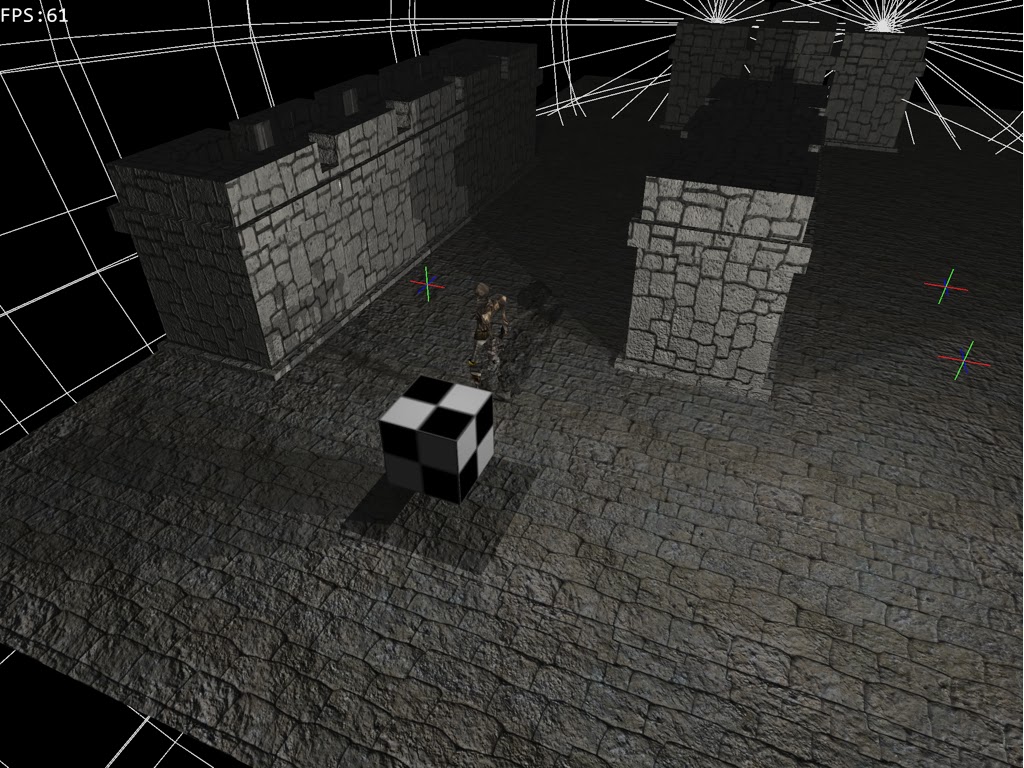

Rendering

Finally, render the shadow volume by updating the index buffer of the shadow VB. The choice of using Z-pass or Z-fail is completely up to the programmer. The same goes for capping the shadow volumes or not. If you need robust shadow volumes, in a scene where the camera might enter the shadow volume, them you will need to cap the volume and possibly use Z-fail. For a top view scene, such as in an RTS game, capping is not required and the volume can be rendered using Z-pass. There are several specializations of these algorithms, I’ll list some resources about them at the end of the post.

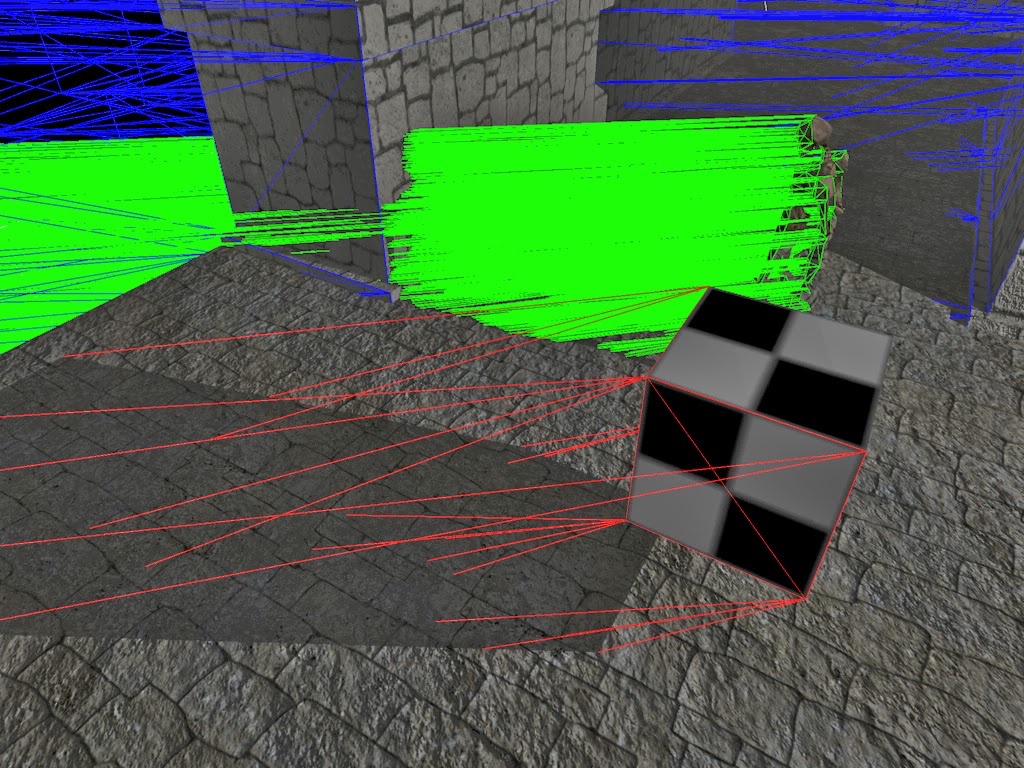

Eye candy

As we can see above, the shadow volume can be heavily tessellated for some meshes. It is crucial to keep the data traffic low between CPU and GPU. That is why using the indexed shadow vertex buffer approach pays off.

Shadow edges are always hard with shadow volumes. Actually, they are accurate to the pixel. This can be good or bad, depending on the tessellation of the meshes. There are some approaches to soften or smudge the shadow edges. I’m most certainly investigating some in the future…

With three point lights enabled, all with shadows, and a few shadow casting objects in the scene, the performance is pretty good. Actually, on my test hardware there is no frame drop at all. I didn’t try to test the limit of light/objects I could achieve, since this is no good measure, except for the power of a specific video card, but overall, I’m pretty happy with the performance of this technique. Fill-rate might be an issue if many shadow casting surfaces are used, but I suspect the limit is quite high. There is no issue with fragment processing though, since the stencil rendering pass does not write to the color framebuffer. This makes the technique appealing even for the last & current gen consoles.

Overall, I think shadow volumes are still interesting and certainly quite usable, even though the game industry seem to have moved away from them.

References

More useful links: