Studying Open Source game engines is a great learning tool for any game developer, specially for game programmers. Luckily we have a few good ones to look into, even though it is only a tiny fraction of the number of games out there that go Open Source. One of my favorites is the DOOM 3 Engine, AKA id Tech 4. Even if somewhat old by now, it was a very solid and well written game engine and it still offers a lot of knowledge about game programming.

Whenever I start looking into a new game engine, I like to begin with the core and support systems. They usually set the tone for the rest of the codebase and tend to be the most modularized parts that are the easiest ones to grasp for an outsider. Id Tech 4 has a very nice pair of support libraries called the idlib and the framework. I suggest forking the GitHub repo and checking out for yourself. The code snippets I’ll show here are taken from the DOOM 3 BFG source-code repository.

idlib is full of interesting stuff, but one little container class caught my eye

the first time I looked into the engine: idHashIndex. This class caries a header

comment that reads:

Fast hash table for indexes and arrays.

Does not allocate memory until the first key/index pair is added.

When I tried to look at the implementation for the first time to find out what made it a “fast hash table”, (or rather, what made it faster than a regular hash table?), I was a bit thrown off by code involving bitwise operations and multiple underlaying arrays. So I just left it be and moved on to look at other stuff. This hash-table-like class is used in many places by the game and engine code. They pretty much use it anywhere a key+value store is required, so it must be a pretty efficient container.

Anyways, the other day I was watching this interesting CppCon talk by Chandler Carruth

where he ranted a couple times about how much the std::map and std::unordered_map

suck for not being designed in a cache efficient way (to sum up, map is a binary

tree, while unordered_map is a linked hash table, so both rely on sparsely allocated

nodes). After watching the talk on YT I immediately remembered about the mysterious

idHashIndex and was prompted to do some digging into that class to find out what

really makes it tick and check to see if it would beat the C++ equivalents

(map and unordered_map) this many years after it was first written.

Figuring out idHashIndex

idHashIndex is not your usual hash table in the sense that it stores pairs of keys and values.

The name is fitting, as it actually stores integer numbers (indexes) that are themselves indexed by a hash key.

So the idea it that you will always use idHashIndex combined with an array that stores the

actual values (the value store), while the hash-index will provide a quick way of mapping an

arbitrary key into a value in that array.

We can already begin to see how it might be more efficient. The “hot” lookup data is kept separate from the values, so you waste no CPU cache with unneeded data related to the values when looking up by key. When we are looking up a key+value store we only care about the keys, so it is a design mistake to marry both the keys and the values under the same structure. This is one of the examples Mike Acton uses in his Data-Oriented Design and C++ talk.

So the overall usage pattern on idHashIndex is this:

- Values are kept in a separate array (usually a dynamic array, like

std::vector) - The hash-index provides a way of mapping keys (like a

std::string) to a corresponding index into the value-store array/vector.

For instance, this is how they use a hash-index to lookup models by name in the engine:

// Lookup code:

idRenderModel * idRenderModelManagerLocal::GetModel( const char * modelName ) {

// some other stuff ommited...

int key = hash.GenerateKey( modelName, false );

for ( int i = hash.First( key ); i != -1; i = hash.Next( i ) ) {

idRenderModel * model = models[i];

if ( strcmp( modelName, model->Name() ) == 0 ) {

// some other stuff ommited...

return model;

}

}

}

// Insertion code:

void idRenderModelManagerLocal::AddModel( idRenderModel * model ) {

hash.Add( hash.GenerateKey( model->Name(), false ), models.Append( model ) );

}In the above example, pointers to models are stored in a models vector-like container,

while the hash-index provides lookup by the filename. hash is a idHashIndex instance.

GenerateKey() just computes a hash value for the input string. It has no business being

a member of the idHashIndex class really, but for some reason they decided to go strict

OOPy there and made the hash function a public member of the class.

Now let’s take a look at the hash-index interface. I stripped all the comments and some irrelevant methods and constructors for brevity. You can find the original at the source repo.

class idHashIndex {

public:

void Add( const int key, const int index );

void Remove( const int key, const int index );

int First( const int key ) const;

int Next( const int index ) const;

void InsertIndex( const int key, const int index );

void RemoveIndex( const int key, const int index );

void Clear();

void Clear( const int newHashSize, const int newIndexSize );

void Free();

int GetHashSize() const;

int GetIndexSize() const;

void SetGranularity( const int newGranularity );

void ResizeIndex( const int newIndexSize );

int GetSpread() const;

int GenerateKey( const char *string, bool caseSensitive = true ) const;

int GenerateKey( const idVec3 &v ) const;

int GenerateKey( const int n1, const int n2 ) const;

int GenerateKey( const int n ) const;

private:

int hashSize;

int * hash;

int indexSize;

int * indexChain;

int granularity;

int hashMask;

int lookupMask;

static int INVALID_INDEX[1];

void Init( const int initialHashSize, const int initialIndexSize );

void Allocate( const int newHashSize, const int newIndexSize );

};The most interesting methods to note are First() and Next(). We can also see that they are

used in the lookup example above. They are necessary because the internal hash-index tables have

a finite size, so eventually a hash key produced by GenerateKey() will collide with an already

in-use entry. For those cases, a short search must be performed until either the wanted item is found

or the end of the buckets chain is reached (-1). This is similar to the idea of Open Addressing.

In the average case, when the load factor of the hash-index is low, the lookup loop will only perform

a single iteration, finding the wanted element in the first try. Thus we have constant-time lookup, like

in any hash table implementation. The performance gain should come from the worst case when the loop has

to iterate several times. Thanks to the way idHashIndex is implemented, subsequent iterations will

access neighboring elements in the array, which are already likely to be in the CPU cache due to hardware

prefetching. This is the departure from std::unordered_map, for instance, which is implemented in terms

of a liked list. The first lookup it constant time, but if there’s a key collision, then a linked-list

iteration is required. Unless the user provides a custom pool allocator, the list nodes will be sourced

via operator new, so unordered_map will potentially touch memory that is scattered through the RAM,

while idHashIndex will only visit neighboring items in the user-defined value-store array.

Let’s now take a closer look at how idHashIndex is implemented and how they made some

clever little optimizations to make lookup as efficient as possible:

// idHashIndex member data:

int hashSize;

int * hash;

int indexSize;

int * indexChain;

int granularity;

int hashMask;

int lookupMask;

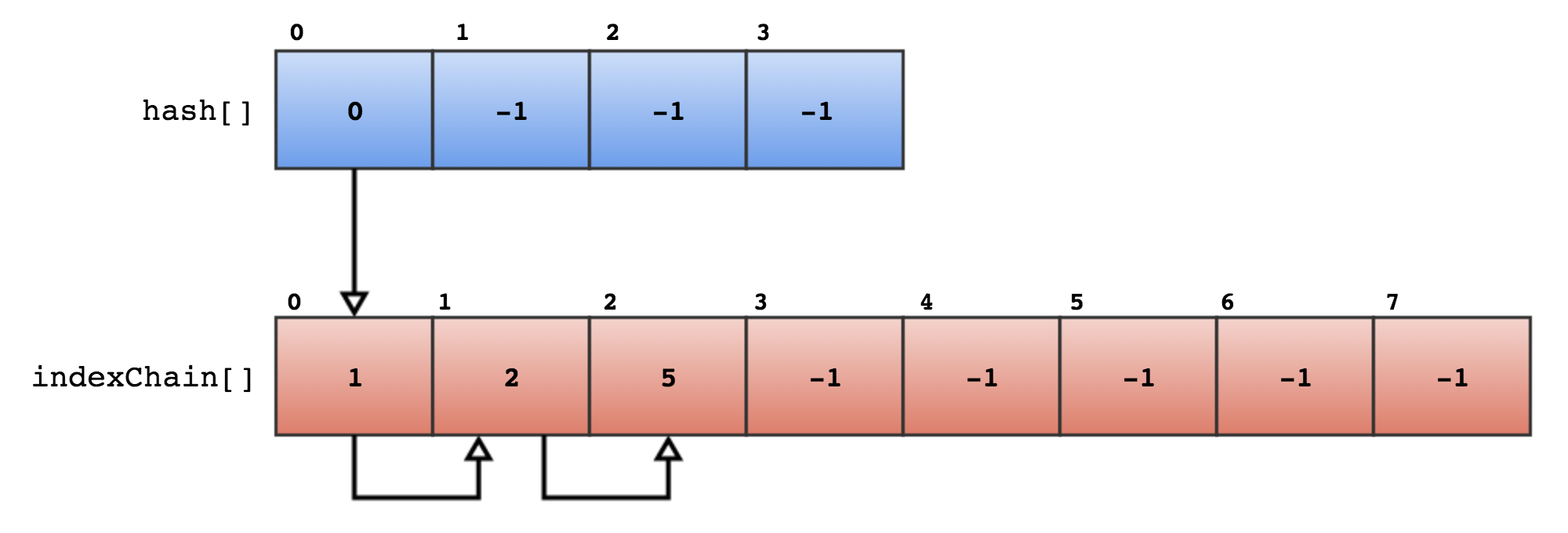

static int INVALID_INDEX[1];hash and hashSize are a pointer to an array of integers and the array size, respectively.

hash[] is indexed by the incoming hash key in methods like First() and Add/Remove. It either

holds the index of the requested data in the user-defined value-store if the keys never collided,

or an index into indexChain. The hash-index has no way of knowing if the value of hash[i] is

and index into indexChain or the user array, that’s why you need to perform the test yourself

in the lookup loop. If the data it returned was the corresponding data for the key, then it was

a user index, otherwise, it points to indexChain and you should call Next().

indexChain and indexSize are also a pointer to an array of integers and the array size.

indexChain[] is either empty (full of -1s) or it has the data for key-collision resolution.

When hash[] points to indexChain[], the given entry will be != -1. If you test indexChain[i]

with your array and find the item you wanted, then it was the index of the data, otherwise,

the resulting value is another index into indexChain[]. Keep looking up with Next() until

you either find the data or until -1 is encountered.

granularity is just the resizing factor for indexChain[]. The hash[] array size will

remain unchanged after the table is constructed, but for the above collision resolution to

work, indexChain[] size must match the size of the external value-store, so whenever a new

index is added to the hash-index, a check is performed to see if the new index will fit the

index chain, if not, indexChain[] is resized to match, with some extra taken from granularity

to amortize future growths of the array.

Now comes a little bit of old school black magic… This is what First() and Next() look like:

int idHashIndex::First( const int key ) const {

return hash[key & hashMask & lookupMask];

}

int idHashIndex::Next( const int index ) const {

assert( index >= 0 && index < indexSize );

return indexChain[index & lookupMask];

}hashMask, lookupMask and INVALID_INDEX are basically an effort to make those two methods

as fast as possible. They effectively allow implementing lookup without using any if tests, which

back then was a bigger deal than it is today. Nowadays you don’t pay much for a jump instruction,

but nonetheless, they are actually very elegant optimizations once you get the gist of it.

INVALID_INDEX is a static array with one element that is set to -1, the “invalid index” sentinel

value used by the hash-index. When the hash-index is empty and no heap memory is assigned to it, both

hash and indexChain will point to INVALID_INDEX, having a single element array with a -1 in it to return the

expected value if a lookup is performed in the empty table. The INVALID_INDEX is never changed by the code but

it is not declared as const because it has to be assigned to the non-const pointers of hash and indexChain.

hashMask will always be the same as hashSize-1. hashSize is enforced to be always a power-of-two,

which means the expensive integer modulo operation (%) can be replaced with a cheap AND (&) with the

length of the table -1 when indexing it. So the cached hashMask also avoids and extra subtraction when

indexing the hash[] array from an incoming hash key.

Now lookupMask was a bit mysterious at first. I didn’t really get the point of it until I actually ran

the code in a few tests. lookupMask will always be set to either 0 or -1. It is of type int, and

this is important. It’s sole objective it to avoid the need for an extra if test for the empty hash-index

case. When empty, lookupMask is 0, so the AND op we see above will always yield zero, which is the only

index available in INVALID_INDEX and equals to -1, the correct value to return for the empty case.

When not empty, lookupMask is -1. If we remember how signed integers are represented in two’s complement, we can see why.

-1 is represented as all 1s in binary, or 0xFFFFFFFF... in hexadecimal. ANDing a bit with 1 will yield back

the input, so when the table is not empty, the AND with lookupMask is just a no-op. This smart little

hack makes the code branch-less by trading a compare and jump for a much cheaper AND instruction.

Benchmarks

Okay, now that we have a pretty good idea of how idHashIndex works and why it might be faster than

the Standard C++ equivalents, it’s time to write up a few benchmarks and stack up std::map,

std::unordered_map and idHashIndex side-by-side.

I made some changes to idHashIndex so that it would compile as a standalone class and wrote

a small test program to stress insertions, erasure and lookup. The hash-index is paired with a

std::vector in my test code, while std::map/unordered_map are used as standalone containers.

The benchmark code was built and tested on Clang with -03. These are the results:

Insertion:

testing insertions on std::map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 372 ns lowest time sample...: 145 ns largest time sample..: 9461 ns ---------------------------------- testing insertions on std::unordered_map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 212 ns lowest time sample...: 133 ns largest time sample..: 80079 ns ---------------------------------- testing insertions on hash_index + std::vector 4096 iterations average time taken...: 82 ns lowest time sample...: 23 ns largest time sample..: 53708 ns

Erasure:

testing erasures on std::map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 308 ns lowest time sample...: 166 ns largest time sample..: 9216 ns ---------------------------------- testing erasures on std::unordered_map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 177 ns lowest time sample...: 157 ns largest time sample..: 281 ns ---------------------------------- testing erasures on hash_index + std::vector 4096 iterations average time taken...: 45 ns lowest time sample...: 22 ns largest time sample..: 80 ns

Lookup:

testing lookup on std::map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 220 ns lowest time sample...: 123 ns largest time sample..: 9021 ns ---------------------------------- testing lookup on std::unordered_map 4096 iterations average time taken...: 488 ns lowest time sample...: 60 ns largest time sample..: 16152 ns ---------------------------------- testing lookup on hash_index + std::vector 4096 iterations average time taken...: 76 ns lowest time sample...: 43 ns largest time sample..: 401 ns

std::map as expected lost on all three operations. It only won at the worst case insertion time.

Map is implemented as a binary search tree (usually a Red-Black balanced tree), so

it allocates sparse node structures for each new key-value pair in the tree. This will have terrible

data locality. My guess is that it only won in the worst case insertion because it always allocates

a new node for each insertion, so the cost is pretty much distributed evenly, while unordered_map

probably only allocated memory at construction, but it might grow the table if needed, thus the

huge spike for the worst time, which is probably resulting from a realloc and copy of the whole table.

Our hash_index (AKA idHashIndex) also measures the time to push_back() in an accompanying std::vector

that acts as our backing store of values.

On average, hash_index proved to be significantly faster than std::unordered_map and much

faster than std::map for the common operations of insertion, removal and lookup. I am definitely

curious to use it again in a more practical scenario and try to compare it again with its closest

Standard sibling, the unordered_map.

Extras

idHashIndex seems like a pretty handy tool to have, after looking at the tests above,

so I went ahead and extracted the code into a standalone single-file template class that

I can now use for my own projects! If you’d like to use it as well, you’ll find it together

with the test and benchmark code in my GitHub repository. I have kept

the GPL license though, to comply with the license used by the DOOM 3 project. So that might

limit its uses a little, I’m afraid. If that is not a problem for you, then please, make

it useful and send feedback!

Watch list

Three very relevant presentations, available on YouTube, I mention above that are worth watching for anyone interested in C++ and optimizations: