- The PlayStation 2 System

- Glossary of terms

- Programming the PlayStation 2 hardware

- Architecture of a program

- Online resources

It’s been a while since I last wrote about my attempt to code a simple PS2 game using the unofficial tools available on the Internet. I had to switch focus to more pressing issues and ended up putting this toy project in the background. I’ve recently resumed work on it and have made some progress since. In this post I’ll talk a little about some of the peculiar aspects of PlayStation 2 development and hardware. I’ll also talk about my impressions with the PS2DEV SDK, the unofficial PlayStation 2 development kit, a few pitfall and difficulties encountered so far and how I’ve worked around them.

The PlayStation 2 System

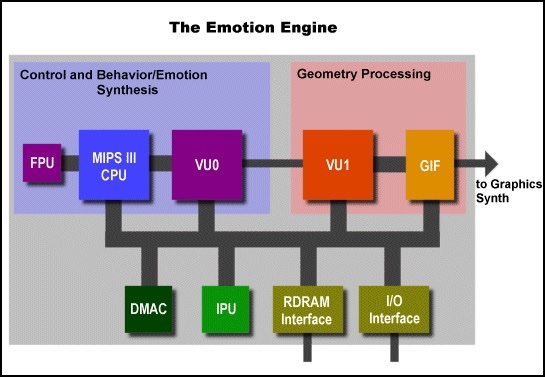

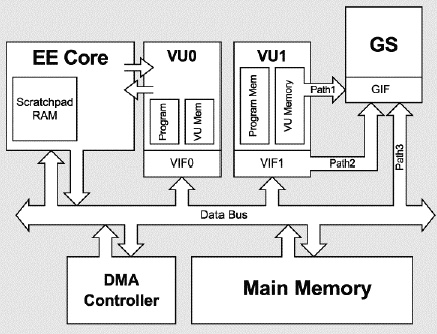

The PlayStation 2 Console is a collection of different processors and dedicated chips attached together in the same box. The following diagrams have been reproduced in several places and depict well the overall architecture.

PlayStation 2 “Emotion Engine”. Source: Google Images.

PlayStation 2 “Emotion Engine”. Source: Google Images.

PlayStation 2 System Architecture. Source: Google Images.

PlayStation 2 System Architecture. Source: Google Images.

Following, I’ve compiled a small glossary with some frequently used names and abbreviations that pop-up when talking about PS2 hardware. The Wikipedia entry on the subject is also worth a look.

Glossary of terms

EE - Emotion Engine: This is technically the name of the whole set of processors and subsystems that make up the PlayStation 2. However, this name is also frequently used to describe just the main CPU, the MIPS III Processor at the core of the system where your compiled C/C++ program runs. The PS2DEV SDK is divided into libraries for the EE, IOP and VUs. When I refer to the main MIPS Processor in this article, I’ll be using the terms EE or EE CPU to describe it.

IOP - Input/Output Processor: Access to peripheral devices, such the Game Controller and the CD/DVD reader, is done by a co-processor called the IOP. The IOP is a separate MIPS CPU that communicates with the main EE CPU via Remote Procedure Calls (RPC). It uses a dedicated DMA channel called the SIF.

SIF - Serial Interface or Subsystem Interface: Channel of communication between the EE main CPU and IOP co-processor. This is a serial DMA channel where both CPUs can send commands and establish communication through an RPC protocol.

GS - Graphics Synthesizer: The PlayStation 2 “renderer”. This is another co-processor attached to the main EE CPU by a DMA channel. The GS is just a configurable rasterizer and texture mapper, so geometry transformations are not done by it. The GS and the EE communicate via the GIF channel. It also has its own memory space, the Video Memory (VRam).

GIF - Graphics Interface: The DMA channel that connects the EE CPU to the GS co-processor. To draw something to the screen, one must send render commands to the GS via the GIF channel.

VU - Vector Units(s): The PlayStation 2 has two additional SIMD vector co-processors, the Vector Units 0 and 1 (VU0 and VU1). The VU0 is directly connected to the EE CPU and can be accessed by inline Assembly code injected into your C program. The VU1 is a separate processor that is attached to the GS. This unit can only run a local micro-program in its local address space, which makes programming the VU1 a bit harder. The PS2DEV SDK currently provides no support for programming the Vector Unit 1. The VUs and the main EE CPU communicate via the Vector Unit Interface (VIF) DMA channel.

SPU - Sound Processing Unit: Dedicated co-processor that accesses the sound output hardware and provides real-time decoding for some audio codecs.

IPU - Image Processing Unit: Another dedicated co-processor attached to the system. This processor can be used to perform real-time MPEG video decoding.

SPR - Scratch Pad: Extended area of memory visible to the EE CPU. This extended memory provides 16 Kilobytes of fast RAM available to used by the application. Scratch Pad memory can be used to store temporary that data that is waiting to be sent via DMA or for any other temporary storage up to the programmer.

DMA - Direct Memory Access: Wikipedia explains it well.

MIPS - Processor architecture and instruction set: The Wikipedia entry.

Programming the PlayStation 2 hardware

Programming on the PS2 involves writing specific code for a few different processors. Not all processors in the system are programmable, by the way.

The main EE MIPS CPU is where you usually start. This CPU is a generic processor that coordinates all the others. The GCC compiler present in the PS2DEV SDK is capable of generating an ELF executable for the EE from a C or C++ project. This executable is the PS2 application entry point.

The second programmable CPU in the system is the IOP. This processor is also a MIPS CPU, and curiously, it is equivalent to the main CPU present in the PlayStation 1 (PS1). This CPU was probably added to the system for the sake of being able to execute PS1 games and ended up being reused as the IO interface for the peripherals. The PS2DEV SDK also provides a compiler and libraries for writing IOP executables. The IOP programs have direct accesses to the PlayStation 2 hardware and are usually small low-level C or Assembly programs. IOP programs communicate with the EE via the SIF interface, which consists of a Remote Procedure Call (RPC) protocol and channel. The IOP processor has its own memory space and, interestingly enough, can run several programs simultaneously. Each program, also known as an IOP module (a program compiled to the IRX format), can be loaded by an EE command and will remain alive in IOP memory waiting for SIF RPC commands. Each IOP program can be thought of as a separate thread of execution, with its own memory space and a specific channel of communication. Common IOP modules for frequently used stuff such as Controller input and Memory Card IO are already provided by the hard-working hackers of the PS2DEV SDK, so you won’t have to write IOP programs unless you need to interface with some custom peripheral or wish to do it just for the sake of learning.

The Vector Units are also programmable. The VUs can be used in micro-mode and macro-mode. Micro-mode means uploading an

Assembly program directly into the Vector Unit and running it locally. This is the most efficient way of programming the VUs.

Macro-mode means accessing the VU directly by inline Assembly code injected into the main EE C/C++ program. Macro-mode is

obviously only possible with the VU0, since this is directly connected with the EE CPU. The VU1 is a separate processor and

thus only programmable in micro-mode, which makes is a bit harder to make efficient used of it. The PS2DEV SDK unfortunately

doesn’t provide any means of accessing the VU1, so it can’t be programmed without the official SDK/tools. VU1 Assembly programs

must be preprocessed using a tool called the VCL (Vector Unit Command Line) and then built into a binary with an assembler

(ee-dvp-as in the Linux SDK).

These tools compile the Assembly code to a binary format that the main program can load and send for execution in one of the VUs through a DMA transfer. The workflow is similar to using modern shaders in an API like OpenGL, with the extra offline preprocessing steps.

Quite frequently in games the generated VU binary code was embedded into the main executable as an array of bytes, to save time and effort of loading a file. Again, if you’ve ever used OpenGL shaders, you might have written programs where you’ve embedded the shader source code as a C-style string.

The Graphics Synthesizer and the other specialized CPUs are not programmable but are quite configurable and flexible. The GS/GIF interface resembles the old Fixed Function OpenGL pipeline, being a state machine managed by a small set of rendering commands. The main program running on the EE CPU talks to the GS by sending packets of rendering commands and transformed vertexes via DMA transfers.

Architecture of a program

The main PS2 program can be written in C or C++, thanks to the GCC compiler (version 3 of circa 2002) provided by the PS2DEV SDK.

The SDK provides libraries for interfacing with the system and main co-processors. A minimal C Standard Library is also available

and works quite well. An old version of the C++ Standard Library (AKA STL) that ships with that version of GCC is also available,

though I haven’t tested it very thoroughly and I’m not sure if it works. The header-only libraries such as <vector> and <string>

seem to work fine, however, I’m using my own replacements so I don’t have to worry about old implementation bugs and incompatibilities.

The system libraries provided by the SDK are basically thin wrappers to hardware system calls. The PlayStation 2 “Kernel” is just a static library that sits at the same memory space of your application. There is no Operating System running in the background, the Kernel runs together with the main program in the EE CPU. The fact that your program is running exclusively in the hardware allows for optimal usage of the available resources.

A PS2 program starts at a traditional main() function and never returns. To start a new program, the system must be rebooted,

either by the reset switch on the Console or a software reset. Once main() enters the basic built-in IOP modules are already

initialized by the Kernel Library, which gets loaded first. You can then initialize the screen and the GS to start rendering.

The program normally enters an infinite loop shortly after initialization and keeps looping until a system reboot.

With this program layout, things like error handling and resource allocation are done in quite different ways from what a PC programmer might be used to. Most errors are usually unrecoverable, so it is common to just end the program with an error message to the screen and entering an infinite loop, waiting for a hard-reboot.

Static allocation of resources is also very common. You should try to allocate as much data statically as you can. Dynamic memory management can be quite expensive, specially when it comes to fragmentation. Most games probably allocate all memory up-front and then install their own specialized memory allocators. It is also not unusual to allocate some permanent resources that stay in memory for the lifetime of the application.

Video Memory (VRam) is another interesting aspect of the PS2 hardware. The VRam can only be accessed directly by the GS and it is attached to its chip. The GS uses VRam for drawing (framebuffer) and depth testing (z-buffer) and to store user supplied textures. There are only 4 Megabytes of Video Memory, so managing this space efficiently can be quite challenging. Usually, you’ll want to render using two framebuffers (traditional double-buffering scheme). These framebuffers must be allocated in the VRam. You’ll also need a z-buffer if you are drawing 3D. With a standard NTSC resolution of 640x448, there goes almost all of your Video Memory just for the unavoidable housekeeping data. With such setup, you have enough space left for about one “large” texture of 256x256 RGBA pixels. I say “large” because even tough this size might seem ridiculously small today, for the PlayStation 2 era, a 256 square uncompressed texture was considered High Definition.

There are ways to mitigate the texture problem, like using palettized or compressed textures. The GS can render palettized and a compressed format natively. But it doesn’t get much easier when you add mip-maps. Any decent 3D drawing will require some Level-of-Detail to avoid artifacts. The only option left is to constantly stream textures in and out of the Video Memory. Sending a whole RGBA texture down the GIF channel is expensive, so this should be avoided as much a possible. An optimized PS2 game must make good use of batching to avoid as much texture changes as it is feasible.

Rendering is where things start to get interesting. The Graphics Synthesizer is much like a very simplified Fixed Function OpenGL, only missing a Vertex Processor. The GS is capable of rasterize and texture map triangles that are already transformed to screen space, so vertex transform and lighting must be done either by the EE CPU or one of the VUs. This might seem a little intimidating for someone who has never attempted to write a software 3D renderer, however, transforming vertexes is not that complicated. All you need is basic knowledge of linear maths and matrices. Writing a good Vector/Matrix library beforehand really helps in grasping the concepts.

The task of vertex transformation and lighting (if using dynamic lights) is traditionally done by the VU1, since it is connected to the GS, it can act like a “Vertex Shader”, transforming data and passing it along to the rasterizer. Since the PS2DEV SDK lacks some of the tools need for this, the second best option is to transform vertexes in the main EE CPU, using either C/C++ code or some VU0 inline Assembly. This is the approach I’ve taken so far. Performance is not that terrible with this setup. With some further optimizations and more code moved into the VU0, I’m expecting to be able to implement fairly complex scenes with a 30+ FPS average.

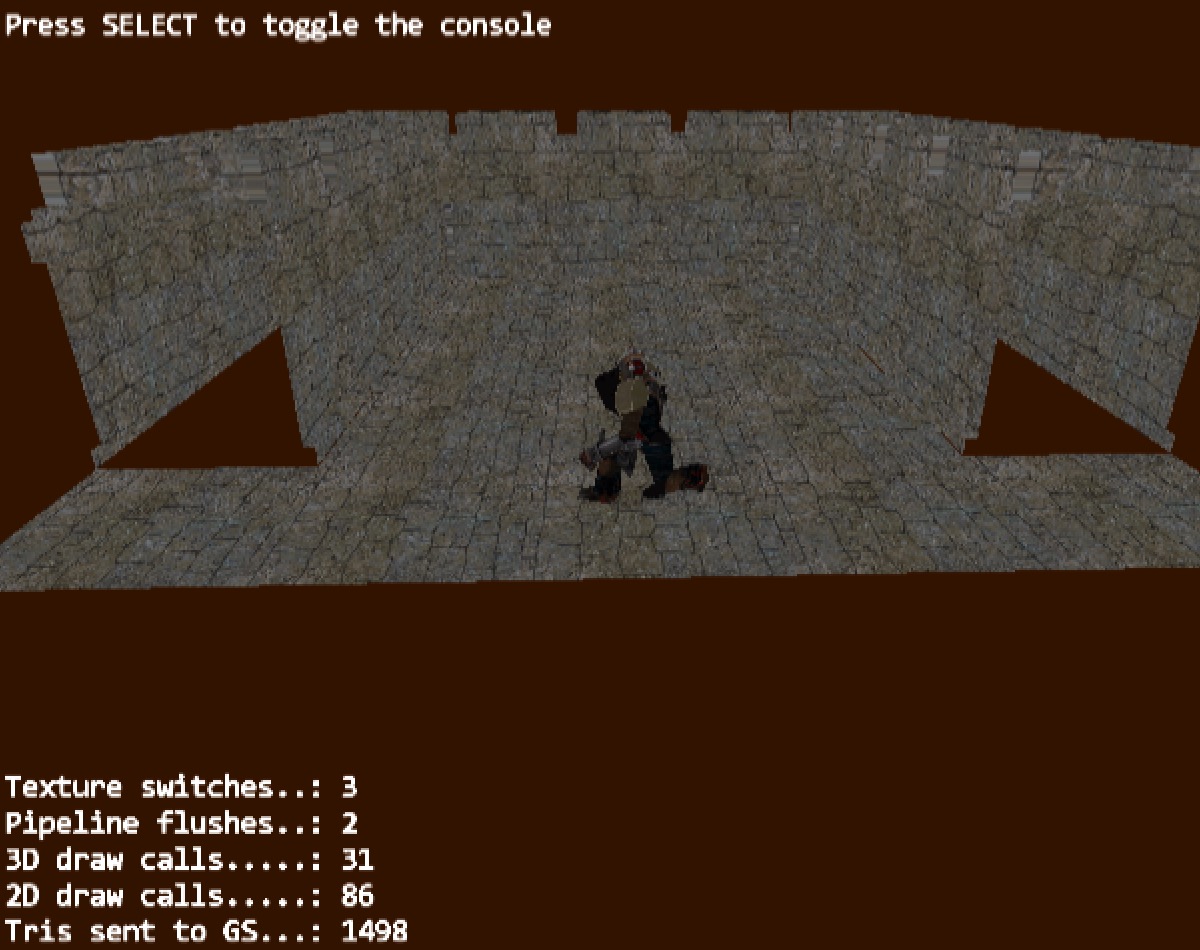

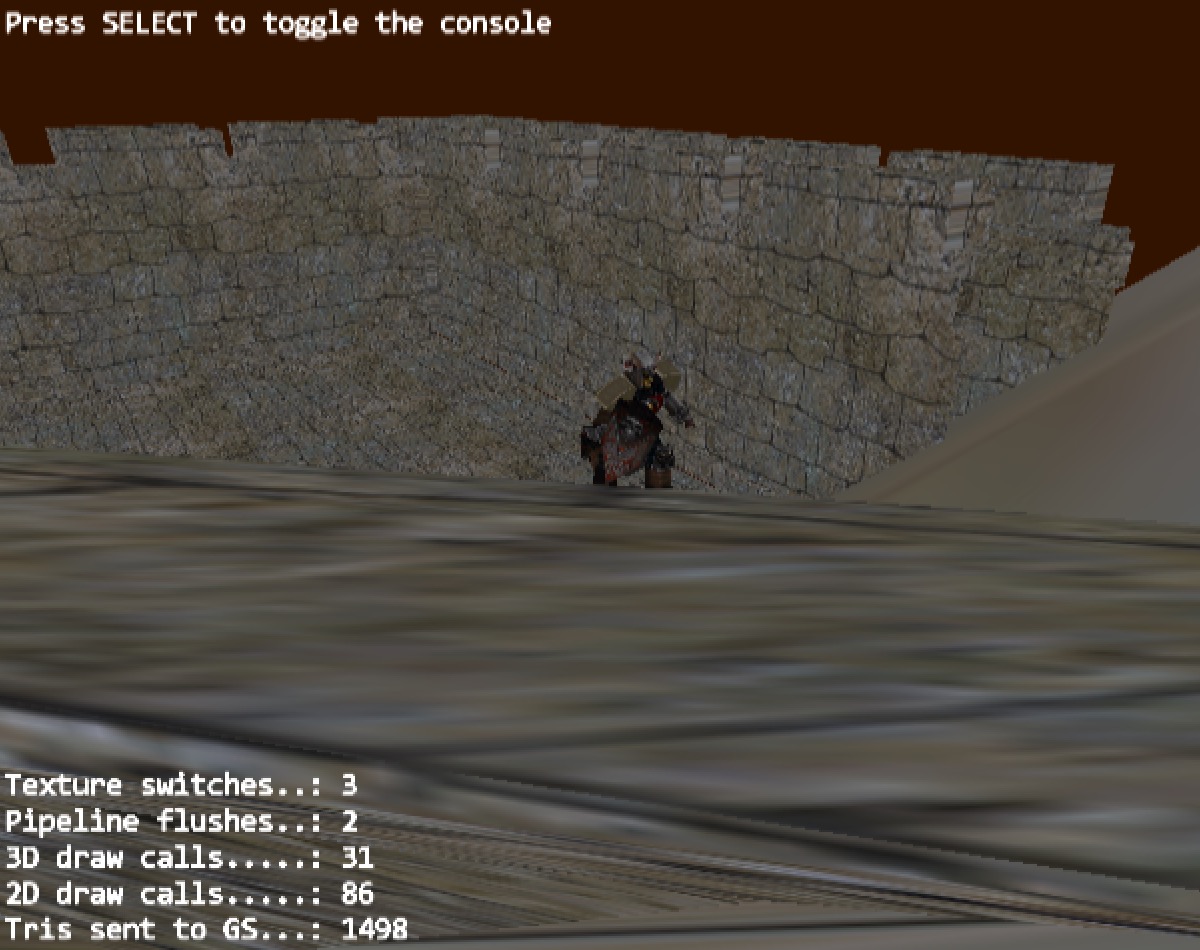

Other seemingly unimportant optimizations, but actually quite necessary, are triangle clipping and back-face culling. In a modern renderer like OpenGL or D3D, we can take these optimizations for granted. In the PS2, you are the responsible for these stages of the pipeline as well. Once you’ve transformed the vertexes, it is up to you to cull them or not. The following is an example of a test scene where back-face culling and clipping are disabled.

Back-face culling disabled.

Back-face culling disabled.

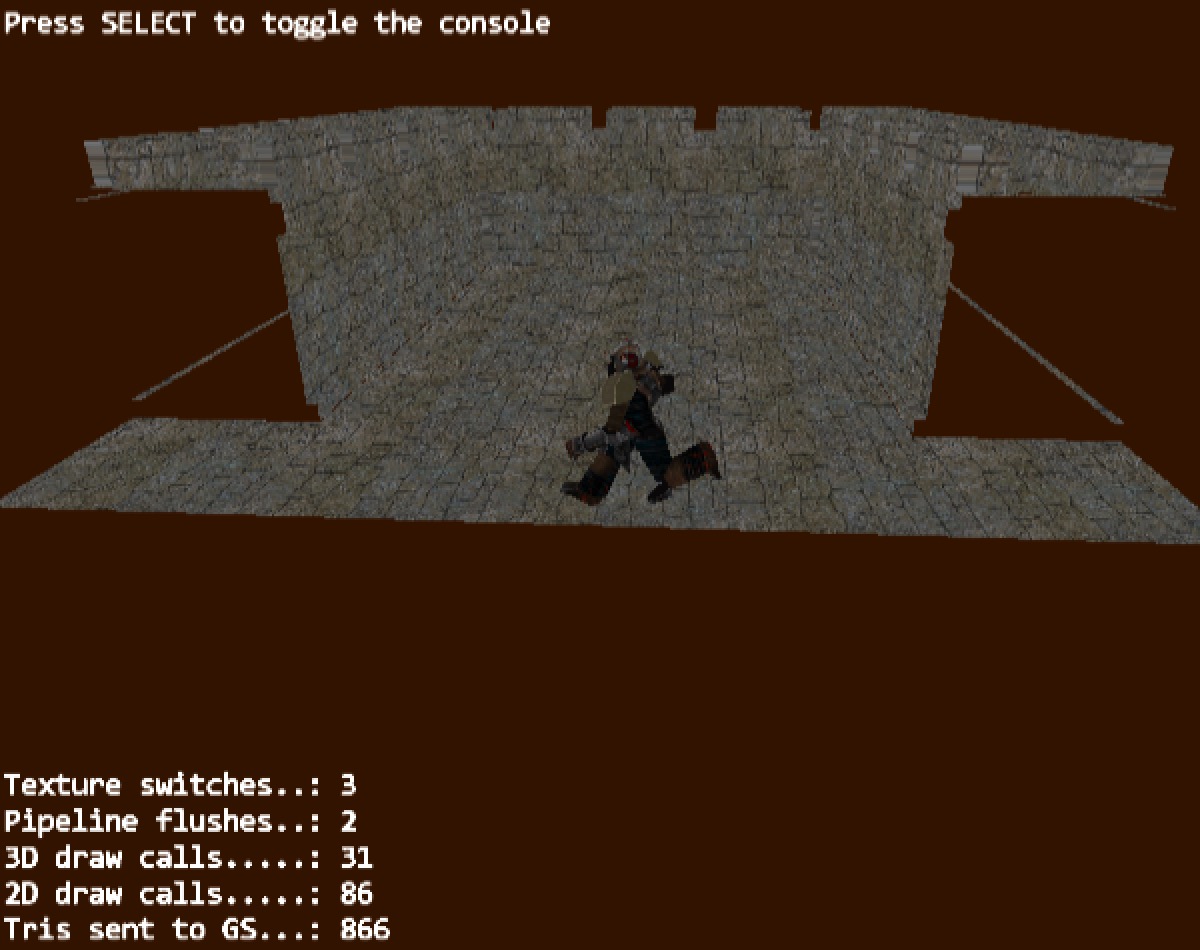

Notice in the bottom left corner the number of triangles that are being drawn (by drawn I mean sent to the GS for further processing). Now compare the same scene with back-face culling and clipping enabled:

Back-face culling enabled.

Back-face culling enabled.

Almost a 50% reduction in the number of triangles sent to the GS for further processing. This makes culling and clipping a necessity for any scene with some occlusion. We can validate that the back-face culling is indeed working by noticing that in the second image above the interior of the walls are not being drawn. I’ve left those corners open so that you could notice the difference.

Back-face culling and triangle clipping will introduce some more processing to the vertex transformation step. This cost can be significant when we are already not using the optimal vertex processing path, however, the sheer number of triangles that we avoid sending to the GS still compensate for the extra EE overhead in most but the simplest scenes.

Back-face culling is a simple operation and also an easy one to optimize. You will need your viewer/camera position to compare with the plane of each triangle being drawn (basically a plane distance test). The cost here lies in ensuring that the viewer and the triangle vertexes are in the same space (either transform the viewer position by the inverse of the model matrix or transform the triangle verts by the model matrix).

Once the spaces match, a simple function like this one can test if the triangle is front-facing and should be drawn or is back-facing and should be discarded:

bool cullBackFacingTriangle(const Vec3 & eye, const Vec3 & v0,

const Vec3 & v1, const Vec3 & v2)

{

// Plane equation of the triangle will give us its orientation

// which can be compared with the viewer's world position.

//

const Vec3 d = crossProduct(v2 - v0, v1 - v0);

const Vec3 c = v0 - eye;

return dotProduct3(c, d) <= 0.0f; // Returns true if it should be discarded

}Vertex/triangle clipping is a little more tricky but just as important. The GS is capable of scissoring vertexes that map outside the rendering window, however, sending vertexes that should have been clipped will usually still produce visual artifacts. Following is an example of a scene with clipping disabled. When parts of the scene get behind the camera, very noticeable visual artifacts start to show.

No off-screen triangle clipping.

No off-screen triangle clipping.

Once vertexes are transformed, the ones that didn’t get clipped/culled must be packed into a fixed point format that the GS can understand and then sent via DMA in a render packet.

The last peculiarity about the rendering is that in actuality all drawing is indirect. Transformed vertexes and render states are always stored into render packets and then flushed to the GS for drawing. The more stuff you batch into a render packet the better (though there is a limit in the amount of data you can send in the GIF DMA channel each transfer). Render packets are just user buffers in main RAM that store data in a GS friendly format. Once a packet is ready, it can be dispatched for GS processing. This opens a lot of doors for parallel rendering. The EE CPU is one thread generating rendering commands and data, while the GS is another thread consuming it. The games with the more stunning visuals in the PS2 are the ones that made good use of these parallelization capabilities present in the system.

Other interesting PS2 development tidbits include, but are not limited to:

Threading

The EE CPU is capable of running concurrent threads. The PS2DEV SDK actuality provides a minimal API for thread creation and management, though I have not tested it and can’t say if it works well enough to be used in a game. I would guess that it is functional enough, since thread creation and destruction is a hardware feature, all that the library has to do is to expose the system calls.

File IO

File IO can be achieved using the standard C FILE API or using a lower-level API provided by the SDK.

File IO must be done by the IOP, since it involves accessing peripheral devices like the Memory Card or Disk.

The file API provided by the PS2DEV SDK wraps all the SIF RPC calls into a friendlier interface, however,

it only provides synchronous file access. Asynchronous file IO can be achieved with direct manipulation of

the RPC/IOP interface. One interesting detail is that file paths in the PS2 have to be prefixed with an

identifier for the source device. So for instance, to access a file in "models/player.obj" that is saved

into a USB mass storage device you would need to pass the path: "mass:/models/player.obj". Some of the prefixes are:

-

"mass:"For the USB mass storage device. -

"mc0:"or"mc1:"Memory Cards slot 0 or 1. -

"cdfs:"The CD/DVD file system. -

"hdd:"The PlayStation 2 compatible external Hard Drive.

Controller Input

Accessing the Game Pads / Controllers is actually quite simple, however, it might involve loading some custom

IOP modules. The Pad Library that comes with the PS2DEV SDK is configured to run with a custom IOP Pad Manager module.

To get this library to work as it is, you must load the custom module into IOP memory by yourself. That works in the

device, but does not work in the Emulator. Since most of my testing is done in the PCSX2 Emulator, I had to circumvent this.

By making some changes in the library I was able to get the Pads to work using the standard sio2man and padman modules

that come with the Kernel and are already loaded when you boot the system. Once that was out of the way, writing a small

class to clean up the Pad input API was a piece of cake.

The Scratch Pad

The PlayStation 2 is well known for its Scratch Pad (SPR) memory. This is sort of an extended CPU cache that is available to the programmer at any time. I haven’t yet found a use for the Scratch Pad in my demos, probably because I haven’t run out of memory yet!

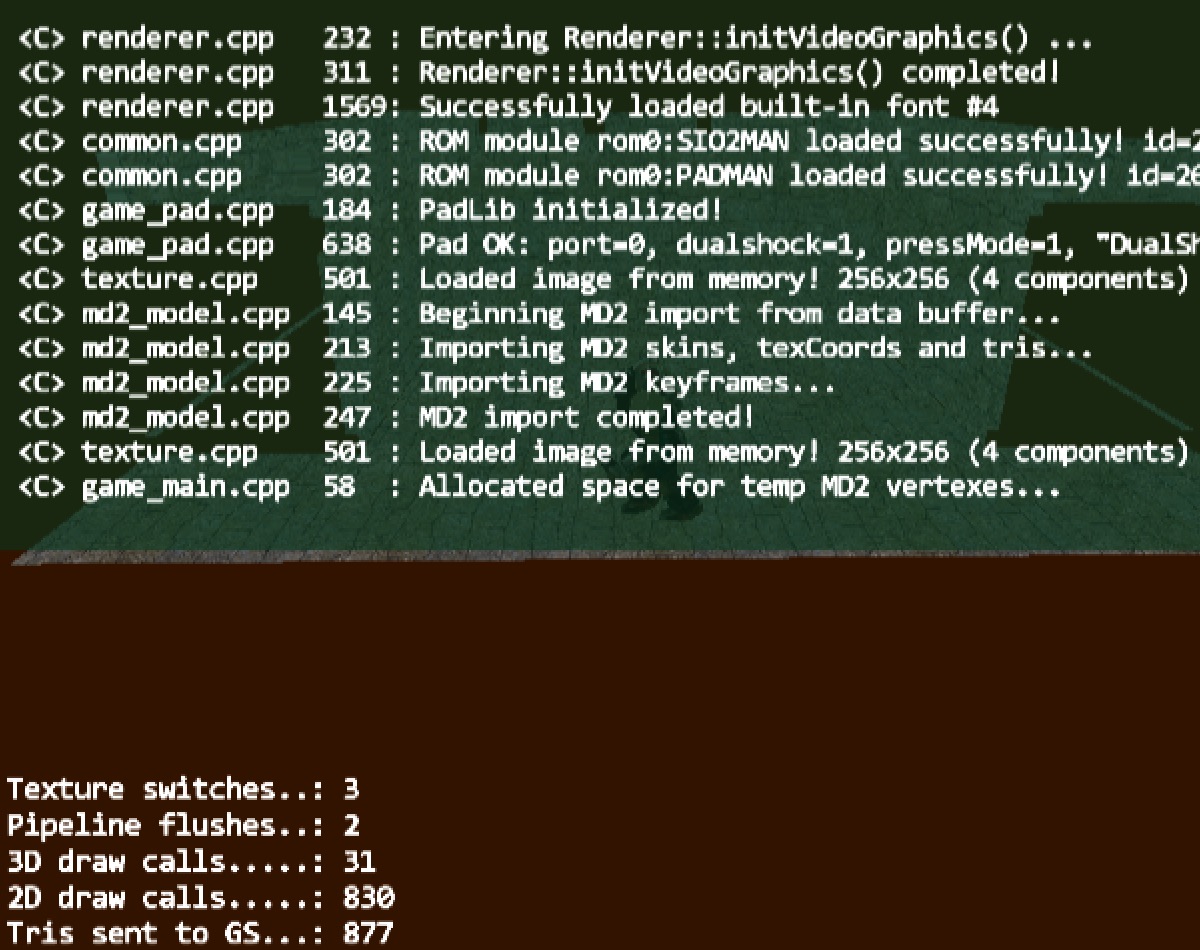

Debugging

Debugging a PS2 application is quite hard. You can kiss goodbye to that nice little GUI-based debugger of Visual Studio or XCode. Even if you are a hardcore GDB user, you are still out of luck. The PS2DEV SDK provides no way of debugging an EE executable. This is comprehensible, since you are cross-compiling. The PCSX2 Emulator wasn’t build for developers so it also doesn’t provide any debugging features. In the end, you are left with the good old “printf debugging”. Your best chance of debugging the program is by printing/logging program states somewhere, to check them after a crash/bug. Visual debugging for the renderer can also be quite useful (drawing lines/points to visualize vectors, directions, bounding boxes).

One approach that I have settled with, and works well for me, was implementing an in-game developer console/terminal (back to Quake, back to the 90’s, awwww yeahhh). In the dev-console I can print logging/tracing stuff as well as verbose debugging, then visualize it in real time as the game runs.

In-game developer console.

In-game developer console.

Online resources

Finally, I’ll list here some of the online resources and documents that have helped me a lot in this hacking endeavor. These websites contain a lot of useful information about the PlayStation 2 System and how to develop games for it with and without the official SDKs.

uLaunchELF

This PS2 application can be burned into a CD/DVD and used to launch your homebrew game into the actual Console. It is very easy to use and supports launching your game from USB flash drives and Memory Cards.

PCSX2

The (unofficial) PlayStation 2 Emulator. Works well on Windows and Mac (systems I have tested it). Using the emulator is the easiest way of testing your game locally, without the hassle of copying it into a flash drive and launching it into the device.

PS2DEV Github Page

This is the home of most Open Source PS2 projects that use the free PS2DEV SDK.

Lukasz.dk: link 1, link 2

A very nice collection of info and articles on however PS2 development, compiled by one of the creators of the free PS2DEV SDK.

Procedural Rendering on the Playstation 2

An interesting old Gamasutra article about procedural generation and rendering using the PS2 hardware. Has a few interesting insights about the platform.

Playstation 2 Linux

Official website of the old PS2 Linux SDK, which was an official SDK provided by Sony that allowed you to install a Linux distro in your PS2 and access some of the hardware. The site is no longer being updated, but it still provides some useful information and even some sample code built using the Linux SDK.

PSX Scene

A forum about hacking and homebrewing for all the Playstation family of Consoles. Not very active nowadays, but might still contain some useful info for “retro-coders”.

PS2link Tutorial

A small tutorial about using the PS2Link tool to send your homebrew executables to the PS2 via network.

I’ve never been able to get it to work properly, but here it is, in case anyone wants to give it a try…

SKS APPS

Website with a few tutorials about how to hack your Playstation to run homebrew software on it. It also has a number of homebrew apps ready to download an test in your Console. Worth the look.

CMSC411

This website presents a comprehensible description of the Playstation 2 hardware.

Playstation 2 Linux Game Programming (Dr. Fortuna’s Website)

UPDATE: The original website is now down but Lukasz has provided a mirror here.

This was a surprising find: A website from a University course that taught game development in the PS2. This site is comprised of several tutorials based on the old official Linux SDK. The tutorials are very well explained and contain a lot of solid information. Source code is provided for all the demos, and even tough the code is written for the Linux SDK, it is quite readable and can be easily adapted for use with the free PS2DEV SDK.

This last one was a life saver for me, since at first I had no access to official documentation and was pretty much left guessing everything by myself.

Happy hackings! Till next time.