- Rendering with the EE + VU0 inline assembly

- World partitioning and collision detection

- Built-in assets

- Fake shadow-blobs and lightmaps

- Particle emitters

- Debugging and frame profiling

- Links to source code

- Running the game

- What didn’t work and TODO

- Videos (recorded from the Emulator)

In my previous post about homebrew PS2 development, I’ve talked about some particular aspects and difficulties of programming a game for this platform using the freely available tools. This will be the last post of this series where I’ll talk a bit about the outcome of this endeavor, a little game demo which I call “The Dungeon Game”.

This tiny game was inspired by classics like Dungeon Siege and Diablo. It features third-person perspective camera, PS2 Controller input, melee combat between player and baddies, particle effects, shadow-blobs and MD2 animations as well as three game levels for you to test your skills!

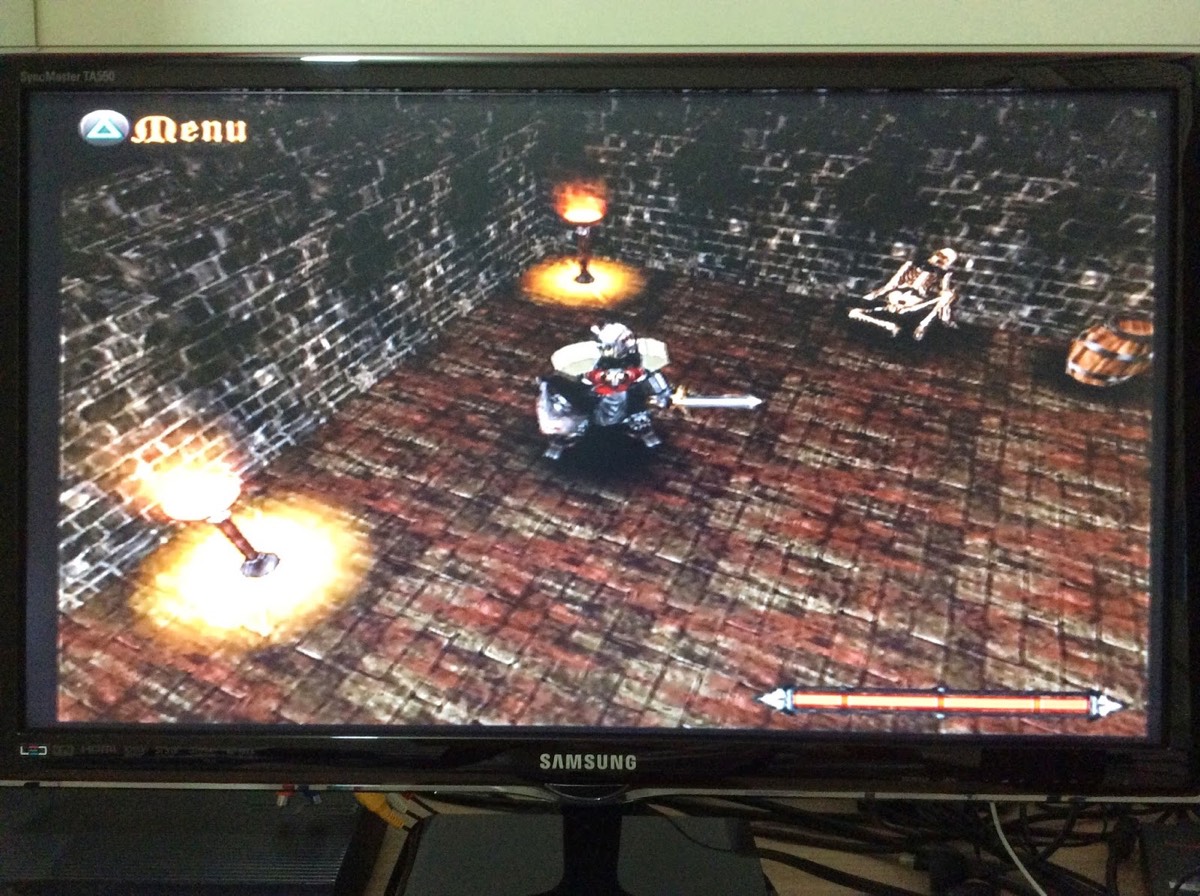

Game running on the PS2 Console & TV.

Game running on the PS2 Console & TV.

Rendering with the EE + VU0 inline assembly

Vertex transform is by far the most expensive stage in rendering with the PS2. The GS rasterizer is very fast and can process a lot of data per frame. The bandwidth for data transfer from the EE CPU to GS is also formidable. You can push a lot of vertex and texture data through the system every frame.

Vertex transform was originally intended to be accelerated by the Vector Units (VUs), however, that requires an official SDK and tools. The best you can do without is use inline VU0 assembly code mixed with your C/C++ program. This is not the optimal way to use the Vector Units, but it is still faster than the code GCC can generate.

The Vector Units have SIMD instructions to operate on one 4D vector at a time, which gives you a nice degree for parallelism.

Both the VUs and the main Floating Point Register (FPR) only operate on single-precision floats, so the double type is not available.

Using the double type in your C/C++ code will compile, but it is automatically converted to a float by the compiler.

The biggest gains I had in the renderer optimizations were in vectorizing the vertex transformations using VU0 inline assembly. Converting matrix/vector multiplication to asm made a big difference. Triangle and vertex culling were also worth optimizing. I’ve also done a lot of inlining for frequently used math and drawing routines, but the gains where marginal, even though GCC did inline most of the code I’ve hinted it to.

The animated 3D models used in the game, as well as a few static props, use the Quake2 MD2 format, which is keyframe based. MD2 animation code is still mostly written in C++, with minimal parts in inline assembly. I’m not sure if there would be a large benefit in optimizing this stage, though it would be worth the try. Since I lacked a more detailed documentation about the VUs and instruction sets, I didn’t put too much effort to this, since it would require a more in-depth knowledge of the system.

The Renderer interface is much like the fixed-function OpenGL or D3D9, where every draw call is “immediate mode”-ish. There are no user-side Vertex Buffers, so drawing always involves passing an array of vertexes to the renderer. This limits porting the game and framework to a modern system without loosing a lot of performance.

World partitioning and collision detection

The game world is composed of a X-Z tile map. Tiles are 3D objects, but have fixed size and are laid-out along X and Z with fixed Y, so in the end this is handled just like a 2D tile map would. Movement is free, not tile-based, so we can have some pretty large tiles the player can walk over. To go from the player’s 3D world position to the tile index it is just a matter of dividing its world X & Z by the fixed tile size and then rounding to the nearest integer. This is of course not 100% accurate when on tile edges, but works fine for my purposes.

Collision is again very simple, using just Axis-Aligned Bounding Boxes (AABB). There is a simple rule that map tiles that are tagged as floor are not collidable (these are the flat ground planes) and tiles tagged as walls are collidable. This is enough to stop the player avatar if it is colliding with a wall, so we keep him inside the world bounds. No need to collide with the floor tiles, since the player is always at the same height (no bumps, floor is always flat / fixed Y position).

Testing collision against every tile and prop in the scene would be expensive, so I’ve decided to apply a simple and cheap world

partitioning scheme to the game. There is always an 11x11 tiles square around the current player’s position that is considered to

be the “active” set of tiles. This set is what gets drawn in the game. Anything further away is automatically discarded. Tiles at

the edge of this active area or pattern are darkened to give a smoother transition. This almost produces a fog-of-war-like effect

that doesn’t look too bad. Collision tests are only done inside this pattern, but actually, there is no need to test for player=>world

collision beyond the 8 tiles that surround the current tile the player is in.

Active set of tiles around the player’s avatar.

Active set of tiles around the player’s avatar.

Built-in assets

Asset management in the Dungeon Game is very peculiar (and a bit unpractical). I’ve decided to make all assets built into the game

executable. So dungeon_game.elf is a stand-alone game executable, no external dependencies required. I took this unusual approach

for two main reasons:

-

It makes the whole game a single file, easier to copy around and test in the PS2 Console.

-

Because file IO did not work in the Emulator. The Emulator is only capable of accessing files inside a CD/DVD or disk image (ISO), so my homebrew apps can’t open loose files in the local File System. Since I did 90% of my development and testing on the Emulator, this was the only workaround I could think of at the time.

This is not very practical for anything much bigger than this demo game though. Compile times suffer with the processing of all that static data and the executable grows huge. Not to mention that every asset chance involves a preprocessing step.

If you look into the dungeon_game/ directory in the source code repository, you should find a raw_assets.zip file in there.

This zip package has all the original MD2/OBJ models and PNG textures that were used in this game. However, the game doesn’t access

this data directly. Instead, each one of those assets was converted to some format that could be built into the source code and

compiled into the ELF executable. If you check the subdirectories inside dungeon_game/ you should find several .h files that

consist of C-style arrays of bytes. Those are the game assets dumped to static C arrays so that they can be compiled into the executable.

So after compiling the game, you end up with a single ELF file that is the whole thing, no external dependencies. The executable

is completely stand-alone and can be run on the Console or Emulator.

Geometry for the map tiles comes from Wavefront OBJ models processed with a custom tool I call obj2c (no source available, sorry!).

An OSX binary of this tool can be found inside raw_assets.zip. The rest of the data was dumped with the freely available bin2c tool,

which can be found here, but also ships with the PS2DEV SDK.

Fake shadow-blobs and lightmaps

The shadows and lightmaps are implemented in such a rudimentary way that I’m almost ashamed about it :P.

I took advantage of the simple layout of the game levels, which are always in a plane (floor tiles have are always flat),

so basically each shadow-blob or lightmap/halo is just a quadrilateral drawn on top of the floor tile. A texture with

translucent alpha is used to color the quadrilateral and the shadow/lightmap plane is drawn with blending enabled.

This had pretty nice results and was reusable for shadows and lights. In the following image you can see the player’s

shadow-blob side-by-side with a light halo texture.

Pseudo lightmaps and shadow-blobs.

Pseudo lightmaps and shadow-blobs.

The light halos are also animated by applying a wobble to the quadrilateral vertexes each frame, based on a simple sine function. This gives the impression that the light/fire is flickering.

That simple setup is also very flexible, basically, any kind of texture can be used as the quadrilateral’s texture map, which allows me to create interesting effects like this rotating circle of power around one of the enemy bosses.

“Circle of power” effect drawn reusing the shadow-blob framework.

“Circle of power” effect drawn reusing the shadow-blob framework.

Particle emitters

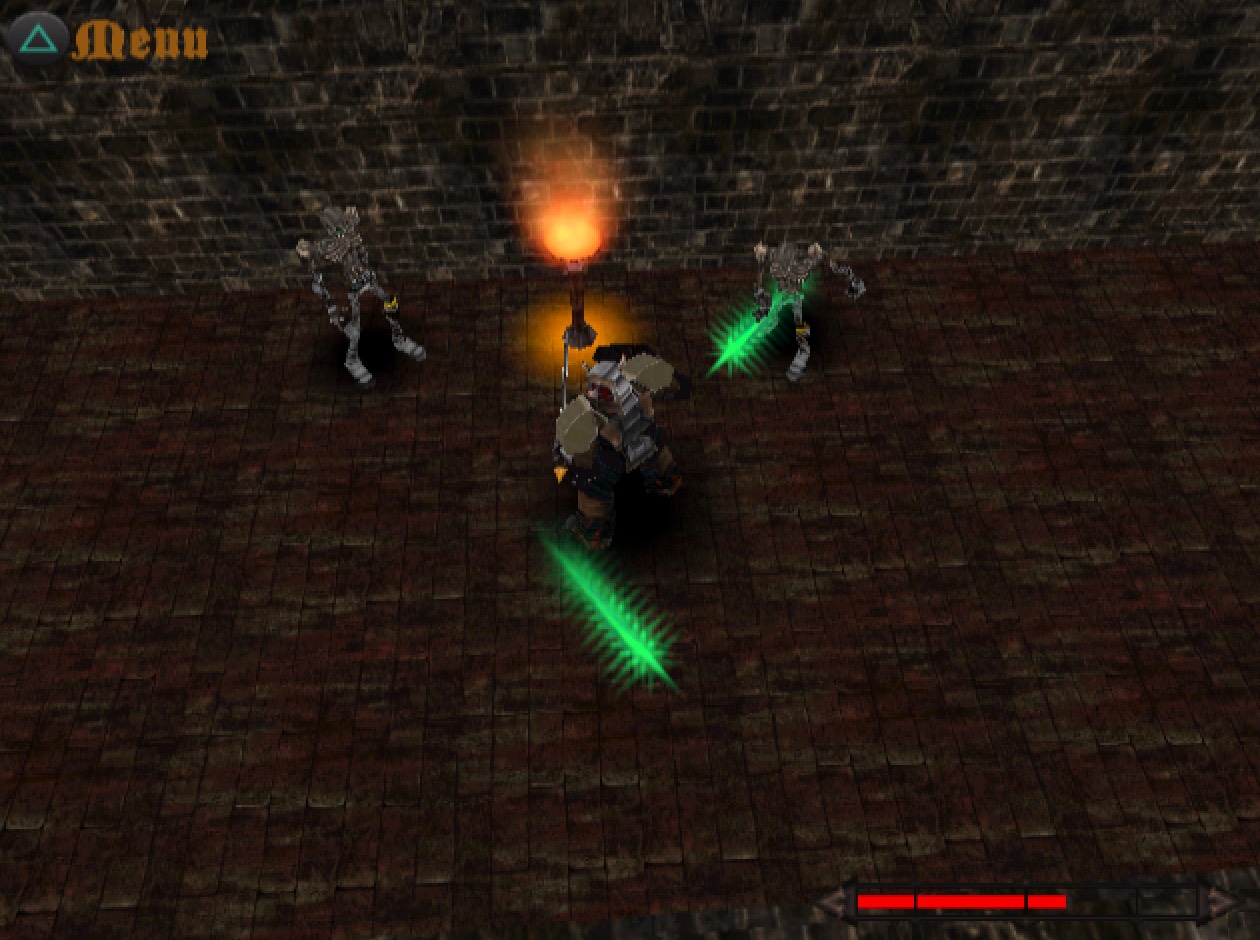

Descent fire and spell effects require particle emitters. In the Dungeon Game I use particles for the fire effect in the torches “lighting” the dungeons and for the enemy attack effects.

Particle effects are used to simulate fire and enemy spells.

Particle effects are used to simulate fire and enemy spells.

Each particle emitter uses billboarded quadrilaterals for the individual particles. The billboards are generated just before drawing, from the particle’s position, size and current camera matrix. I then sort the particles using a custom QuickSort from closest to camera to farthest. Particles are finally rendered with blending enabled and depth-writes disabled. All particle emitters that share the same texture are batched together.

The particle emitters are a pretty expensive part of each scene in the game. The main cost is in the transformation and rendering of the large amount of vertexes for the particle quadrilaterals. By using indexed quads, I can reduce the amount of data that is processed every frame, but still, about four active emitters is the limit before the frame-rate drops below 30fps. I suspect this limit would be much higher if I were to render them using the VU1, but unfortunately I’m stuck with EE + VU0 inline assembly vertex transform, which slows things down considerably.

The optimizations I’ve applied in this stage were to reduce the amount of data handled per emitter as much as possible, to optimize data cache, and only update and render visible particle emitter. Not updating the emitter that are outside the view has the side effect of making effects like the fire in the torches to appear to go off when outside view. Then when they enter view again, you can notice for a couple seconds that the emitter is restarting all over.

This is the bare minimum data for a particle, as far as I could trim it (where Vector is a 3D xyz vector/point):

struct Particle

{

Vector position; // Current world position of this particle.

Vector velocity; // Current velocity vector of this particle.

float size; // Size/scale of this particle (both width and height).

uint durationMs; // Time this particle will go inactive, in milliseconds.

};Debugging and frame profiling

As I’ve mentioned in the previous post on this PS2 homebrew series, the Open Source libraries available are pretty bare and provide little to no debugging tools.

There is no fancy profiler available either, so your best bet is to time your game frames to have a rough estimate of the time taken by each task.

I’ve also replaced all memory allocation functions (including C++ new and delete) with custom

ones that take extra “Tags”, so that I can keep rough estimates of the amount of memory used by each

subsystem and/or task. The tags are simple hardcoded enum constants.

enum MemAllocTag

{

MEM_TAG_GENERIC, // Generic / untagged allocations.

MEM_TAG_CPP_NEW, // Allocated with operator new (generic allocation).

MEM_TAG_GEOMETRY, // Any geometry / vertexes / MD2.

MEM_TAG_TEXTURE, // Textures/images allocated on the heap.

MEM_TAG_PARTICLES, // Particle emitters.

MEM_TAG_RENDERER, // Renderer misc & render packets.

// # entries in this enum. Internal use.

MEM_TAG_COUNT

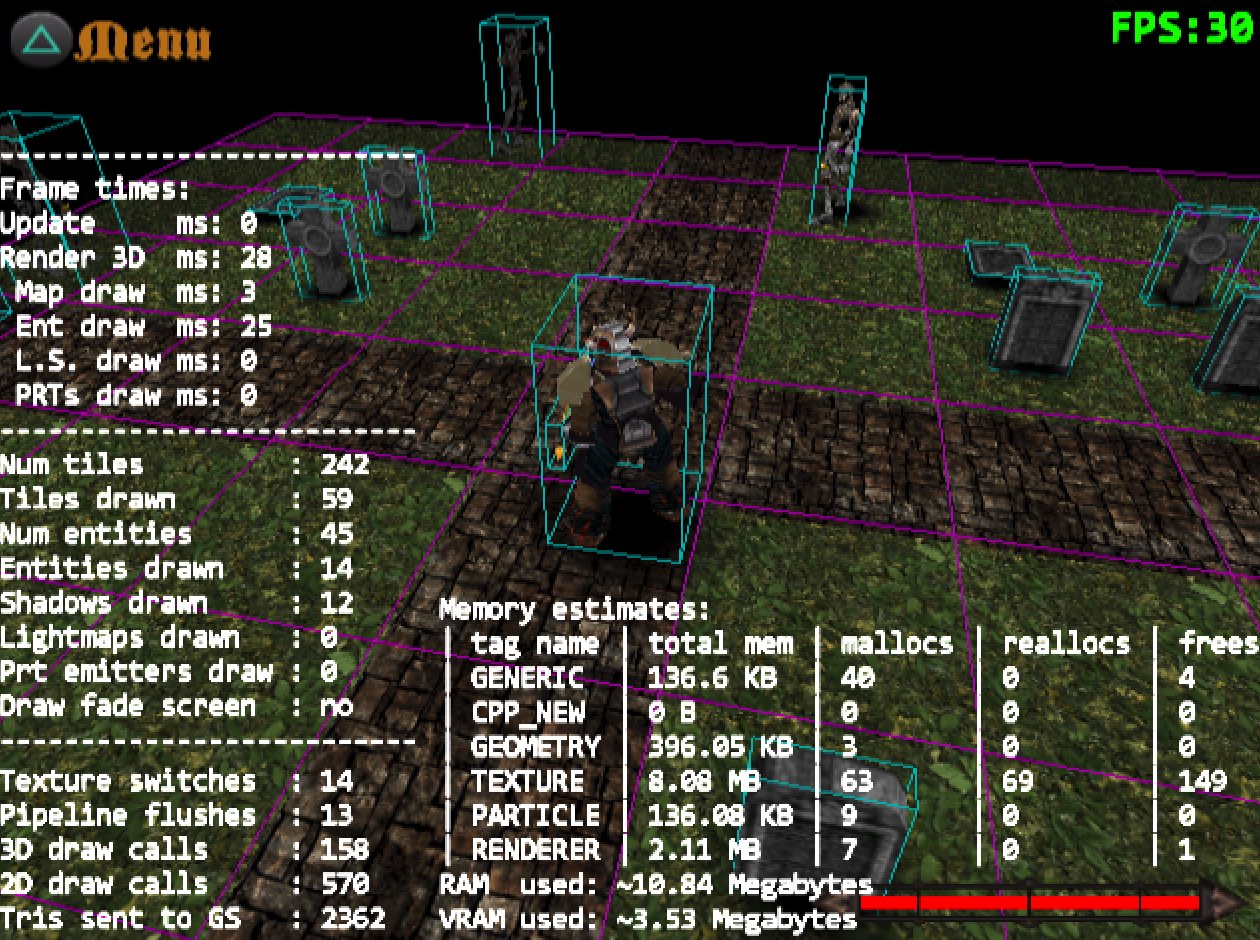

};The following image shows the screen printing of several debug stats that I’ve used to measure the impact of my optimizations. You can also see the debug line drawing for the model AABBs in the background.

Several debug overlays and rendering to aid development.

Several debug overlays and rendering to aid development.

Notice that I’m just above 10 Megabytes of RAM and effectively out of video memory. I was honestly expecting to be out of main RAM much sooner, since I didn’t really bother optimizing for memory usage. That makes me think that you can actually put a lot of content in a PS2 game after all…

Links to source code

Source code for the Dungeon Game and all the other simple demos I wrote using the PS2DEV free SDK are available at this online repository. The game project itself is inside this subdirectory.

Source code is split into a more generic “framework” set of classes and code shared by all the demo apps and code for the specific demos themselves. The framework wraps all the low-level PS2DEV SDK and hardware details, so game code is more portable and only relies on framework functionality.

There are other more detailed README files inside the relevant directories in the repository.

Running the game

I’ve included pre-built ELF executables in the repository. Those executables are stand-alone and ready to play in an Emulator or Console. If you have PCSX2 installed, just fire up the Emulator and choose run ELF, then select the game executable. Sound will probably not work on the Emulator, couldn’t get it to function properly for some reason, so I have disabled it on the Emulator run. It should play fine on the Console.

To run the game or any of the other demos on a PS2, you’ll need a modified (AKA jailbroken) PlayStation that can run homebrew software. Jailbreak unfortunately involved an actual hardware modification in the Console, so if you bought a legit one from an official Sony dealer, you probably can’t run homebrew software in it. If you do have a modified device, then you can use a bootloader such as uLaunchELF to start the Console and then load a homebrew app from a USB stick, memory card or even CD/DVD.

What didn’t work and TODO

Camera and controls for the Dungeon Game are still very crude and need a lot of polishing to be anywhere near a real game. More optimizations in the particle and entity / MD2 model rendering should be done to ensure a smooth 30fps through the game. More stuff converted to inline VU0 assembly should help, though the ideal would of course be to move all the vertex transform to the Vector Unit 1.

Textures are currently NOT mipmapped. There is some VRam left that can be used to store uncompressed mipmaps, I just didn’t try it out because of the lack of documentation and samples in the PS2DEV SDK. The functions for mipmapping are not documented, so getting it to work would consist of a lengthy trial and error processes. Also, a more sensible approach regarding texturing would be to use some native compressed format to save VRam and data transfer.

Sound playing did not work on the Emulator. It fails to load the necessary IOP module. I suspect it has something to do with the Emulator refusing to load/run unofficial IOP programs. The stock IOP modules that ship with the PS2 ROM load just fine. The custom sound module that comes with the free SDK fails to load. So most likely sound playing will fail in the Emulator (it did for me), but should work in the PS2 just fine. This will not prevent the rest of the game from working in the Emulator. Only the sound is compromised.

Videos (recorded from the Emulator)

Following are a couple YouTube videos showcasing the three demo levels I wrote.